DEVELOPMENT OF LAW ON REGISTRABILITY AND PROTECTABILITY OF UNCONVENTIONAL TRADE MARKS SUCH AS SHAPE, SOUND, SMELL, COLOUR AND TASTE IN INDIA, UNITED STATES OF AMERICA AND EUROPEAN UNION

Unconventional Trade Marks is always an interesting topic in Trade Marks Jurisprudence. The ambit of Unconventional trade marks is ever expanding even to consider something as vague as taste. With capitalism ever increasing, it has become increasingly important for the business entities to protect whatever they think if used by another will decrease their sales or dilute their brand. Sometimes, it is just the uniqueness of a sign. For example, the Red Sole shoes of Christian Louboutin. This Article deals with registration requirement and protection afforded to Unconventional Trade Marks such as Smell, Sound, Colour, Shapes and Taste in India, United States of America and European Union. The article deals with the obstacles that arise on account of registration and protection of unconventional trade marks and how the jurisprudence has developed in this regard in these three jurisdictions.

1. INTRODUCTION

A trade mark can be defined as any indicia of origin applied to a product in such a manner which enables the consumer to distinguish between the product of one party from another. As per European Court of Justice (ECJ), the essential function of a trade mark is to guarantee the identity of the origin of the marked product to the consumer or end-user by enabling him, without any possibility of confusion, to distinguish the product or service from others which have another origin.[1]

As per Trade Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights Agreement, 1994 (hereinafter referred to as ‘TRIPS’ or ‘TRIPS Agreement’), a trade mark is:

“Any sign, or any combination of signs, capable of distinguishing the goods or services of one undertaking from those of other undertakings, shall be capable of constituting a trademark. Such sign, in particular words including personal names, letters, numerals, figurative elements and combinations of colours as well as any combination of such signs, shall be eligible for registration as trademarks.”[2]

The first convention which was bought in for the sole purpose of protection of industrial property including trade marks was the Paris Convention for the Protection of Industrial Property, 1883. The term ‘mark’ or ‘trade mark’ was not defined in the said convention. Further as per the Convention the registration formalities in respect of the marks was left to the discretion of the Member States.

As per the said Convention, the condition for the filing and registration of trademarks shall be determined in each country of the Union by its domestic legislation.[3]

Therefore, there was no restriction whatsoever in recognizing any sort of symbol or indicia of origin as marks and provide for their protection, whether it be shape, sound, smell or colour.

Article 15 (1) of TRIPS Agreement permits the members that if the signs are not inherently capable of distinguishing the relevant goods or services, Members may make registrability depend on distinctiveness acquired through use. Members may require as a condition of registration, that signs be visually perceptible.

Therefore, as per TRIPS it is not essential that the mark must be inherently distinctive or that the sign can be graphically represented. However, National Jurisdictions provide for the requirement of graphical representation as a condition of registration with changing dimensions. Therefore, a bare perusal of Article 15 (1) of the TRIPS Agreement makes it clear that non-conventional marks which are not visually perceptible are not completely excluded from the scope of TRIPS Agreement.

Therefore, if a Member State wishes to provide for registration of sound, smell or taste marks it is open for it to do so.

2. DEFINITION OF ‘TRADE MARK’ IN UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, EUROPEAN UNION AND INDIA

The Lanham Act of the United States defines ‘trade mark’ as:

“The term “trademark” includes any word, name, symbol, or device, or any combination thereof:

(1) used by a person, or

(2) which a person has a bonafide intention to use in commerce and applies to register on the principal register established by this Act, to identify and distinguish his or her goods including a unique product, from those manufactured or sold by other and to indicate the source of the goods, even if that source is unknown.”[4]

In 1993, European Union adopted Community Trademark Regulation. Article 4 of the Regulation defines ‘trademark’ as:

“any sign capable of being represented graphically, particularly words, including personal names, designs, letters, numerals, the shape of goods or of their packaging, provided that such signs are capable of distinguishing the goods or services of one undertaking from those of other undertakings.”

which was identical in Trade Marks Directive of 1989[5] and Trade Marks Directive of 2008[6].

It is very pertinent to mention herein that though the United States’ Lanham Act defines trade mark in an inclusive definition which makes it open to expansive interpretation it does not uses the word ‘graphically represented’, the European Union’s Community Trademark Regulation provides as an essential ingredient of ‘graphical representation’ for determination of ‘trademark’.

Till 2015, the Trade Marks Directive of European Union also used the words ‘graphical representation’. However, in 2015, the same has been changed to the following: “being represented on the register in a manner which enables the competent authorities and the public to determine the clear and precise subject matter of the protection afforded to its proprietor” which is generally how graphical representation has been interpreted by European Court of Justice. The definition of the term ‘trade mark’ under Article 3 of the Trade Marks Directive, 2015[7] is as follows:

“A trade mark may consist of any signs, in particular words, including personal names, or designs, letters, numerals, colours, the shape of goods or of the packaging of goods, or sounds, provided that such signs are capable of:

(a) distinguishing the goods or services of one undertaking from those of other undertakings; and

(b) being represented on the register in a manner which enables the competent authorities and the public to determine the clear and precise subject matter of the protection afforded to its proprietor.”

In India, the origin of the Statutory Law of registration and protection of Trade Marks can be stated to be the enactment of Trade Marks Act, 1940. In Trade Marks Act, 1940, the term “mark” had been defined as: “a device, brand, heading, label, ticket, name, signature, word, letter or numeral or any combination thereof”[8]

and “trade mark” had been defined as:

“means a mark used or proposed to be used in relation to goods for the purpose of indicating or so as to indicate a connection in the course of trade between the goods and some person having the right, either as proprietor or as registered user, to use the mark whether with our without any indication of the identity of that person”[9]

The Trade Marks Act, 1940 was repealed by the Trade and Merchandise Marks Act, 1958. The Trade and Merchandise Marks Act, 1958 defined the term “mark” as: “includes a device, brand, heading, label, ticket, letter or numeral or any combination thereof’”[10]

and the term “trade mark” had been defined as:

“means– (i) in relation to Chapter X (other than section 81), a registered trade mark or a mark used in relation to goods for the purpose of indicating or so as to indicate a connection in the course of trade between the goods and some person having the right as proprietor to use the mark; and (ii) in relation to the other provisions of this Act, a mark used or proposed to be used in relation to goods for the purpose of indicating or so as to indicate a connection in the course of trade between the goods and some person having the right, either as proprietor or as registered user, to use the mark whether with or without any indication of the identity of that person, and includes a certification trade mark registered as such under the provisions of Chapter VIII”[11]

In the year 2003, the Trade and Merchandise Act, 1958 was repealed and the Trade Marks Act, 1999 was bought into force and continues to be the prevailing statutory law on the subject in India. As per the Trade Marks Act, 1999, a ‘mark’ includes:

“a device, brand, heading, label, ticket, name, signature, word, letter, numeral, shape of goods, packaging or combination of colours or any combination thereof.”[12] (emphasis supplied)

and the term “trade mark” has been defined as:

“trade mark” means a mark capable of being represented graphically and which is capable of distinguishing the goods or services of one person from those of others and may include shape of goods, their packaging and combination of colours; and— (emphasis supplied)

(i) in relation to Chapter XII (other than section 107), a registered trade mark or a mark used in relation to goods or services for the purpose of indicating or so as to indicate a connection in the course of trade between the goods or services, as the case may be, and some person having the right as proprietor to use the mark; and

(ii) in relation to other provisions of this Act, a mark used or proposed to be used in relation to goods or services for the purpose of indicating or so to indicate a connection in the course of trade between the goods or services, as the case may be, and some person having the right, either as proprietor or by way of permitted user, to use the mark whether with or without any indication of the identity of that person, and includes a certification trade mark or collective mark;”[13]

A perusal of development of statutory law in India makes it clear that in India, in recent times shapes and combination of colours have been sought to be recognized as trade marks. However, as it is an inclusive definition it may include other non-conventional marks subject to them being able to satisfy the test of graphical representation as provided in Section 2 (1) (zb) of the Trade Marks Act, 1999.

3. ADMINISTRATION OF REGISTRATION OF TRADE MARKS IN UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, EUROPEAN UNION AND INDIA

In United States, the United States Patents and Trade Marks Office (USPTO) deals with registration of trade marks in United States. The Appeals against the decision of USPTO examiners lie to the Trade Mark Trials and Appellate Board (TTAB). The decisions of TTAB can be challenged before the United States District Court or the United States Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit.

In European Union, the European Union Intellectual Property Office is the relevant body for registration of Community Trade Marks. It was founded in 1994 and is based out of Spain. It works for all countries of the European Union. It was formerly known as Office for Harmonization in the Internal Market (OHIM) till 2016. The appeals against decision of EUIPO lie to the European Court of Justice. Appeals also lie to European Court of Justice in cases pertaining to regional offices where interpretation of Directives is required as well as from National Courts referring important questions for consideration by European Court of Justice.

It is pertinent to mention that in India, the registration of the Trade Marks is governed by the Trade Marks Office under the Ministry of Commerce & Industry. The Trade Marks Office analyzes the registrability of Trade Marks in the first instance. Any person aggrieved by an order of the Trade Marks Office can approach Intellectual Property Appellate Board (IPAB) by way of a Statutory Appeal. The decisions of IPAB can be challenged before the High Court by way of a Writ Petition.

4. SMELL MARKS

As a marketing strategy, manufacturers of goods introduce smells of scents to make the use of the products more pleasant or attractive. These goods could include cleaning preparations, cosmetics and fabric softeners. Even less obvious goods are now manufactured with particular scents to add to the product’s appeal, for example, magazines, pens, paper and erasers. But practically there exists a problem in recognizing smell as trademark as there is a requirement of ‘graphical representation’, under the Indian law and other legal systems such as the European Union[14]. However, the need for ‘graphical representation’ in relaxed in United States of America.

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

In United States, smell marks have been accorded registration and their registration under the Lanham Act has even been recognized by the Supreme Court of the United States. Although scent marks are not specifically specified in the Lanham Act, United States as a practice acknowledges that scent can operate as a source identified where is had no utility function.[15]

First time a registration was accorded to a smell mark in United States was in the year 1990 by the decision of Trademarks Trial and Appellate Board.[16] In this case, the issue was whether a scent mark is distinctive because it is unique in nature or unique to the market. [17] The product in question was manufactured sewing thread and embroidery yarn and the description given to the smell was: “a high impact, fresh floral fragrance reminiscent of Plumeria blossoms.”

The first examining authority rejected the claim for registration of the smell mark on the ground that the same did not indicate the origin of the product and also did not distinguish is from product of other competitors in the market, i.e. to say that the applicant could not show as to how the scent was linked to the origin of product. Further, the application was rejected on the ground that the applicant did not mention the fragrance on its packaging.

The Applicant filed an appeal before the Trademarks Trial and Appellate Board and argued that the Applicant’s embroidery yarn was the only embroidery yarn in the market which was scented and the scent was a high impact, fresh, floral fragrance reminiscent of Plumeria blossoms.

The Trademarks Trial and Appellate Board overturned the decision of the Examining Authority and the fragrance was given a trade mark on the ground that scent is capable of distinguishing certain type of products and the Applicant was the only one who was manufacturing a year with a scent. The TTAB also noted that the Applicant had advertised yarn with scent features and demonstrated that consumers recognized the scent as an indicator of origin.[18]Further, the Court made the distinction between a smell that is used which is not an inherent attribute of the product and fragrances for products like perfumes, cologne etc. where smell is an essential ingredient of the product.[19]

This decision of TTAB in In re Clarke; 17 U.S.P.Q. 2d 1238 was recognized and acknowledged by the Supreme Court of the United States in Qualitex Co. v. Jacobson Prods. Co.[20]

The United States Patents and Trade Marks office (USPTO) requires for the purposes of according registration to smell marks a substantial amount of evidence to establish that a scent or fragrance function as a mark.[21]

EUROPEAN UNION

In European Union, an essential feature of a trade mark is graphical representation which is evident from a perusal of Article 4 of the European Union Community Trade Marks Regulation as provided earlier. Therefore, the first recognised case of registration of a smell mark in the European Union came under the scanner of the Examiner on the ground that the description provided by the Applicant does not make the mark capable of graphical representation.[22]

However, before we delve into this case, it very pertinent to mention that to implement the European Community Directive, UK enacted the United Kingdom Trade Marks Act, 1994 under which Chanel’s Application for registration of the scent for Chanel No. 5 was rejected on the ground that the same is functional as the fragrance is the product itself.[23]

In the Venootschap onder Firma Senta Aromatic marketing’s Application[24], Applicant filed an appeal before the Office for Harmonisation of Trade Marks (OHIM). In the said case, the Applicant applied for registration of a smell mark with the description ‘THE SMELL OF FRESH CUT GRASS’ for tennis balls. The Examiner was of the view that the words ‘the smell of fresh cut grass’ is not a graphical representation of the smell mark itself and the mark as applied for in fact description of the mark. The Examiner refused the registration by holding:

“In my view, the mark has not been represented graphically. An olfactory mark has been claimed and a verbal description of the mark has been given. But where is the mark itself? What has been given appears to be a graphic representation of a report of what the mark is, and not the mark itself. Indeed, being a verbal report of what the mark is, it is not clear where the scope of protection begins and ends. In what way for example does the “smell of fresh cut grass” differ from fresh grass or just cut grass? Would the scope include cover for the words themselves?”

The Second Board of Appeal overturned the Examiner’s decision and observed:

- It is first necessary to consider the purpose of the ‘graphical representation’ requirement contained in Article of Community Trade Marks Regulation.

- The purpose is to enable proper examination, search and oppositions by the office or potential opponents, as the case may be.

- There are no rules laid down in Regulation concerning representation of olfactory/smell marks.

- The question to be decided is whether or not the description in the application gives enough information to those reading them to walk away with an immediate and unambiguous idea of what the mark is when used in connection with tennis balls.

- The smell of freshly cut grass is a distinct smell which everyone immediately recognises from experience.

- For many, the scent or fragrance of freshly cut grass reminds them of spring, or summer, manicured lawns or playing fields, or other such pleasant experiences.

- Description provided for the olfactory mark sought to be registered for tennis balls is appropriate and complies with the graphical representation.

The question of registration of smell marks again came before the European Court of Justice in Sieckmann v. Deutsches Patent-und Markenam[25] where the Applicant intended to register an olfactory/smell mark, before the German Patent and Trade Marks Office, in Classes 35, 41 and 42 for which the Applicant provided the following description:

“Trade mark protection is sought for the olfactory mark deposited with the Deutsches Patent- und Markenamt of the pure chemical substance methyl cinnamate (= cinnamic acid methyl ester), whose structural formula is set out below. Samples of this olfactory mark can also be obtained via local laboratories listed in the Gelbe Seiten (Yellow Pages) of Deutsche Telekom AG or, for example, via the firm E. Merck in Darmstadt.

C6H5-CH = CHCOOCH3”

Subsequently, the Applicant made the following addendum to the description:

“The trade mark applicant hereby declares his consent to an inspection of the files relating to the deposited olfactory mark “methyl cinnamate” pursuant to Paragraph 62(1) of the Markengesetz and Paragraph 48(2) of the Markenverordnung (Trade Mark Regulation).”

The Applicant also submitted a sample of the smell in a container snd submitted that the scent was usually described as “balsamically fruity with a slight hint of cinnamon”.

The German Patent and Trade Marks Office refused the application on account of graphical representation and non-distinctiveness. In appeal, the Federal Patents Court, Germany was of the view that:

- In theory, odours may be capable of being accepted in trade as an Independent means of identifying an undertaking.

- Mark in question would be capable of distinguishing the services and would not be regarded as purely descriptive of the characteristics of services.

- However, it is doubtful whether the olfactory mark such as that in issue can satisfy the test of graphic representability which is essential even if the smell has become accepted in trade as belonging to a specific undertaking.

The, Federal Patents Court, Germany stayed the proceedings and referred two questions for determination to European Court of Justice. The same are reproduced herein below:

“(1) Is Article 2 of the First Council Directive of 21 December 1988 to approximate the laws of the Member States relating to trade marks (89/104/EEC) to be interpreted as meaning that the expression “signs capable of being represented graphically” covers only those signs which can be reproduced directly in their visible form or is it also to be construed as meaning signs — such as odours or sounds — which cannot be perceived visually per se but can be reproduced indirectly using certain aids?

(2) If the first question is answered in terms of a broad interpretation, are the requirements of graphic representability set out in Article 2 satisfied where an odour is reproduced:

(a) by a chemical formula; (b) by a description (to be published); (c) by means of a deposit; or

(d) by a combination of the abovementioned surrogate reproductions?”

The European Court of Justice answered the first question by stating that Article 2 of the Directive must be interpreted as meaning that a trade mark may consist of a sign which is not in itself capable of being perceived visually, provided that it can be represented graphically, particularly by means of images, lines or characters, and that the representation is clear, precise, self-contained, easily accessible, intelligible, durable and objective.

The reasoning of the European Court of Justice to arrive at such a finding can be summarized as under:

- That Article 2 of the Directive does not expressly exclude smell marks and thus Article 2 has to be interpreted to include a trade mark which is not capable of being perceived visually, but can be represented graphically.

- Graphic representability determines the precise subject of protection afforded to registered proprietor and thus enables the competent authorities to fulfill their obligations to examination of marks while further ensuring that the competitors or other members of the public have knowledge of rights of the registered proprietor without subjectivity.

The European Court of Justice answered the second question by stating that in respect of an olfactory sign, the requirements of graphic representability are not satisfied by a chemical formula, by a description in written words, by the deposit of an odour sample or by a combination of those elements.

The reasoning of the European Court of Justice to arrive at such a finding can be summarized as under:

- Only few people will be able to recognize the odor by way of formulae.

- A formula does not represent the odour but the substance and is not sufficiently clear and precise.

- The description provided is not sufficiently clear, precise and objective.

- Sample of odour does not constitute graphical representation and is not sufficiently stable or durable.

- If the above three constituents, by themselves cannot satisfy graphic representability, a combination of the same will not be able to satisfy requirement of clarity and precision.

From the above discussion of precedents in European Union, it can be concluded that registration of smell marks is permissible in European Union but they should not be functional and should be very precise, certain, intelligible and capable of ascertainment so even if they are not visually perceptible they can be graphically represented. The Seickmann case[26], has laid down a very rigid test for graphical representation of a smell mark, which is so stringent that on paper, European Union recognizes smell marks as trade marks but the tests laid down for its registrability have made registration of the said marks virtually impossible. This is for the reason that the chemical formulae as well as storage of sample as tests have been completely rejected. The description test is subjective and it is highly difficult to describe a smell with exact precision.

Interestingly, the amended definition of ‘Trade Mark’ in the European Union Directive of 2015[27] does not include smell but includes other non-conventional marks such as sound, colour combinations etc. The graphical representation requirement has been re-worded to “being represented on the register in a manner which enables the competent authorities and the public to determine the clear and precise subject matter of the protection afforded to its proprietor” and hence the Seickmann test should continue to apply on Smell marks.

INDIA

Smell trade marks as per the draft of Manual of Trade Marks Practice & Procedure applicable to India, consumers of fragranced goods are unlikely to attribute the origin of the products to a single trader based on the fragrance. As per the Draft Manual, for purposes of registration as a trade mark, unless the mark is ‘graphically represented’ it will not be considered to constitute as a trade mark. Accordingly since smell marks do not meet this requirement, under the Indian trademark system.[28]

5. SOUND MARKS

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

As early as in 1978, in In re General Electric Broadcasting Company, Inc.[29], the Applicant filed an application to register a mark consisting of the sound made by a Ship’s Bell Clock as a service mark for Radio Broadcasting Services. The mark was described as “a series of bells tolled during four, hour sequences, beginning with one ring at approximately a first half hour and increasing in number by one ring at approximately each half hour thereafter”. Along with the application, the Applicant filed a tape recording. The Examiner refused the registration on the ground that sequential sounds sought to be registered do not and cannot constitute a mark serving to identify Applicant’s services. The Examiner observed that the Applicant is doing no more than telling its listeners the time by broadcasting the traditional maritime sequence.

The Applicant appealed against the said refusal. The Board observed the following on registrability of sound marks:

- The mark need not be confined to a graphic form.

- Sound marks can be registered when they are used in such a manner so as to create in hearer’s mind an association of sound with a service.

- However, a distinction must be made between unique, different or distinctive sounds and those that resemble or imitate “commonplace” sounds or those to which listeners have been exposed under different circumstances.

- This does not mean that sounds that fall within the latter group, when applied outside the common environment, cannot function as marks for the services in connection with which they are used.

- However, the arbitrary, unique or distinctive marks are registrable as such on the Principle Register without supportive evidence, those that fall within the second category must be supported by evidence to show that purchasers and listeners do recognise and associate the sound with services offered and/or rendered exclusively with a single, albeit anonymous, source.

The Board applied the said tests in the present case and held that:

- The fact that Applicant’s sound mark is a play on the traditional ship’s bell clock sounds does not mean that in the environment of radio broadcasting services; it is incapable of functioning as a mark to identify such services.

- This is manifestly a question of fact, and in view of the experience of the average person with ship’s bells, whether as a member of the armed forces or otherwise, evidence in such a situation is necessary to establish that the ship’s bell sounds have become distinctive of Applicant’s services and do, in fact, identify and distinguish Applicant’s broadcasting services to those exposed to such services, That is, the sounds ring a bell for the listener.

In the present case, there was no evidence to satisfy the above test and hence the refusal of registration was affirmed.

Thus, key take away from the said decisions can be:

- In United States, there is no requirement of graphical representation in case of Sound Marks

- They are registrable provided they distinguish goods/services of one from another.

- There is a recognition for 3 (three) categories of sounds marks: a) unique, different or distinctive; b) “commonplace” sounds; and c) “commonplace” sounds to which listeners have been exposed under different circumstances.

- In case of first category no evidence of distinctiveness is required. In case of other two categories evidence of distinctiveness through use is required.

Further sound marks were specifically recognised as valid trade marks by the United States Court of Appeals in Astrud Oliveira v. Frito Lay, Inc.[30] The Court observed that there is no reason as to why compositions to serve as a symbol or device to identify a person’s goods or services and is protectable under the Lanham Act. The Court relied on the Supreme Court Decision in Qualitex Co. v. Jacobson Products Co. Inc.[31] which in turn recognizes that the United Stated Patents and Trade Marks Office grants protection to shape, smell and sound marks.

In Kawasaki Motors Corp USA v. Harley-Davidson Michigan Inc[32], the Applicant sought for registration of the exhaust sound of the motorcycle, produced by a V-Twin common Crankpin Engine[33] registration of a sound mark was challenged on the ground of functionality. It was contended by the Opponents that all the V-Twin common crankpin Engines will make the same sound and thus the sound is functional and cannot be attributable to the Applicant. However, no decision was arrived at in the said matter as the Applicant has abandoned the application before a decision could be arrived at.

From a perusal of the above decisions it can be ascertained that the Courts or the Trade Mark Board in America do protect sound marks. Further, the ‘graphical representation’ requirement is not a concern as sonograms and sound recordings have been accepted for the purposes of registration.

EUROPEAN UNION

The Position of the European Union can be determined by the perusal of the decision of the European Court of Justice in the case of Shield Mark BV v. Joost Kist[34]. In the said case, the Registrant (Shield Mark BV) of the mark had 14 registered trade marks in its favour granted by Benelux Trade Marks Office. The registrations were in Class 9 (computer software (recorded), etc.), 16 (magazines, newspapers, etc.), 35 (publicity, business management, etc.), 41 (education, training, organization of seminars on publicity, marketing, intellectual property and communications in the business sector, etc.) and 42 (legal services).

The details of the same in their form and manner of presentation in application are provided herein below:

- Four on a Musical Stave – The trade marks consisted of the representation of the melody formed by the notes (graphically) transcribed on the stave.

- Four other trade marks consisted of the first nine notes of Für Elise. The trade mark consisted of the melody described, plus, in one case, played on a piano.

- Three further marks consist of the sequence of musical notes E, D#, E, D#, E, B, D, C, A. The trade marks consisted of the reproduction of the melody formed by the sequence of notes.

- Two of the trade marks registered by Shield Mark consisted of the denomination Kukelekuuuuu (an onomatopoeia suggesting, in Dutch, a cockcrow)

- Last mark consisted of a cockcrow and also stated: Sound mark, the trade mark consists of the cockcrow as described.

In October 1992, Shield Mark launched a radio advertising campaign, each of its commercials beginning with a signature tune employing the first nine notes of Für Elise. From February 1993, Shield Mark issued a news sheet describing the services which it offers on the market. The signature tune is heard each time a news sheet is removed from the stand. Further, Shield Mark also published softwares for lawyers and marketing specialists and each time the disk containing the software started a cockcrow was heard.

Mr Kist, was a communications consultant, in particular in advertising law and trade marks law. During an advertising campaign in 1995, Mr Kist used a melody consisting of the first Nine notes of Für Elise and also sold a computer program which on emitted a cockcrow. Shield Mark brought an action against Mr Kist for infringement of its trade mark and unfair competition. Court of the Hague, Netherlands ruled in favour of Sheild Mark on the basis of law of civil responsibility but dismissed its claims based on trade mark law on the ground that it was the intention of the Governments of Members of Benelux to refuse to register sounds as trade marks.

Shield Mark BV appealed to the Supreme Court of Netherlands, which stayed the proceedings and referred some questions to the European Court of Justice for determination. The same are reproduced herein below:

“1. Must Article 2 of the Directive be interpreted as precluding sounds or noises from being regarded as trade marks?

2A. If the answer to question 1(a) is in the negative, what requirements does the Directive lay down for sound marks as regards the reference in Article 2 to the need for the sign to be capable of being represented graphically and, in conjunction therewith, as regards the way in which the registration of such a trade mark must take place?

2B. In particular, are the requirements referred to in (a) satisfied if the sound or the noise is registered in one of the following forms: musical notes; a written description in the form of an onomatopoeia; a written description in some other form; a graphical representation such as a sonogram; a sound recording annexed to the registration form; a digital recording accessible via the internet; a combination of those methods; some other form and, if so, which?”

The Court answered the first question by stating Article 2 of the Directive is to be interpreted as meaning that sound signs must be capable of being regarded as trade marks provided that they are capable of distinguishing the goods or services of one undertaking from those of other undertakings and are capable of being represented graphically. The ECJ also held that the Member States cannot preclude such registration as a matter of principle.

The reasoning of the European Court of Justice to arrive at such a finding can be summarized as under:

- The Court followed the Sieckmann Case[35] where it held that olfactory marks are capable of registration as they are not expressly excluded from Article 2 of the Directive. Similarly, as sound marks were not expressly excluded they were held to be under the realm of Article 2 of the Directive.

- The Intervening Member States argued that sound signs are not by nature incapable of distinguishing the goods or services of one undertaking from those of other.

The Court answered the second question by stating that Article 2 of the Directive must be interpreted as meaning that a trade mark may consist of a sign which is not in itself capable of being perceived visually, provided that it can be represented graphically, particularly by means of images, lines or characters, and that its representation is clear, precise, self-contained, easily accessible, intelligible, durable and objective;

In the case of a sound sign, those requirements are not satisfied when the sign is represented graphically by means of a description using the written language, such as an indication that the sign consists of the notes going to make up a musical work, or the indication that it is the cry of an animal, or by means of a simple onomatopoeia, without more, or by means of a sequence of musical notes, without more. On the other hand, those requirements are satisfied where the sign is represented by a stave divided into measures and showing, in particular, a clef, musical notes and rests whose form indicates the relative value and, where necessary, accidentals.

The Court did not rule on the aspect whether filing of an application by way of sonogram, a sound recording, a digital recording or a combination of those methods would be acceptable for accepting an application for registration of a sound mark in lieu of ‘graphical representation’ as the same was hypothetical to the facts as Shield Mark BV never applied for registration of its sound marks through these modes.

The reasoning of the European Court of Justice to arrive at the finding in the second question can be summarized as under:

- The Court followed the Sieckmann Case[36] and said that a trade mark may consist of sign which is not capable of being visually perceived provided that it can be represented graphically, particularly by means of images, lines or characters, and that its representation is clear, precise, self-contained, easily accessible, intelligible, durable and objective.

- Those conditions are also binding on sound signs

- A graphical representation such as the first nine notes of Für Elise or a cockcrow at the very least lacks precision and clarity and therefore does not make it possible to determine the scope of the protection sought

- A sequence of notes without more, such as E, D#, E, D#, E, B, D, C, A is neither clear, nor precise nor self contained and does not make it possible to determine the pitch and the duration of the sounds forming the melody.

- Lack of consistency between the onomatopoeia itself, as pronounced, and the actual sound or noise. Thus, where a sound sign is represented graphically by a simple onomatopoeia, it is not possible for the competent authorities and the public to determine whether the protected sign is the onomatopoeia itself, as pronounced, or the actual sound or noise. Furthermore, an onomatopoeia may be perceived differently.

- A stave divided into bars and showing, in particular, a clef (a treble clef, bass clef or alto or tenor clef), musical notes and rests whose form (for the notes: semibreve, minim, crotchet, quaver, semiquaver, etc.; for the rests: semibreve rest, minim rest, crotchet rest, quaver rest, etc.) indicates the relative value and, where appropriate, accidentals (sharp, flat, natural) ─ all of this notation determining the pitch and duration of the sounds ─ may constitute a faithful representation of the sequence of sounds forming the melody in respect of which registration is sought. This mode meets the requirements of the Court.

- Even if such a representation is not immediately intelligible, the fact remains that it may be easily intelligible, thus allowing the competent authorities and the public to know precisely the sign whose registration is sought.

As this case did not dealt with sonogram (sound spectogram), the issue whether a sound mark is capable of registration by way of depiction through sonogram came up in Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer Lion Corporation’s Appeal relating to Community trade mark application No. 143891[37]. The issue arose as the subject application was not for music in traditional sense and hence musical notation (approved test for graphical representation of a sound mark in Shield Mark BV[38]) was not available. In the said case, the Applicant sought to register the famous MGM Roar of Lion as a trade mark and represented the same through a spectrogram in the application. The same is reproduced herein below:

In the application the mark was described as “sound produced by the roar of a lion and is represented by the spectrogram abovementioned”. The examiner refused the registration on the following grounds:

- No correlation between reproduction of the mark and its description

- Public was not able to perceive the sound from the representation even if it read with the description.

- The description does not allow to reproduce clearly, precisely and unequivocally the sound as depicted.

- The mark does not fulfill the requirements of the function of a trade mark. It is not capable of distinguishing the goods or services of one from others. The public will not determine the origin of these goods upon sight of this mark. The sign applied for is not precise, clear and unequivocal enough to be perceived per se by the public as being a specific ‘roar of a lion’.

The Applicant filed an Appeal. In December 2000, the appeal was re-allocated to the newly established Fourth Board of Appeal.

The Appeal was rejected as the sonogram was incomplete and had no representation of scale on time axis and alleged frequency axis. It was held that a pattern that cannot be read, and therefore not understood, cannot be considered as a valid graphic representation of a mark.

Apart from the same, the Board of Appeal of OHIM held as follows otherwise on position of law of registering sound marks through sonograms or other methods which depict graphically sound such as oscillogram and spectrum:

- The fundamental registrability of sound marks is not disputed, as a trade mark may consist of a sign which is not in itself capable of being perceived visually, provided it can be represented graphically.

- In this context, particular account should be taken of the high standards developed by the Court of Justice for the quality of the graphic representation which must be clear, precise, self-contained, easily accessible, intelligible, durable and objective.

- If the sound mark involves music in the traditional sense of the word, there is an obvious way to represent it graphically by representing the theme or composition by standard musical notation.

- On the other hand, the situation is different when it is not music, in the traditional sense of the word, but animal noises such as the roar of a lion or rolling thunder in a storm. Here, representation by musical notation regularly fails to work.

- Oscillogram would be suitable to represent a sound mark graphically only if it were exclusively a question of the strength (volume) of the signal, which is clearly not the case with sounds.

- A spectrum is also only a two-dimensional depiction of the distribution of a signal’s frequency content (vertical axis) versus frequency (horizontal axis). Therefore same would be suitable only if changes in frequency content over time were irrelevant, as is obviously not the case with sounds and noises.

- Graphic representation of a noise – such as a lion’s roar or a roll of thunder – by means of a sonogram results from analysis of the pitch (frequency), relative volume (frequency content) and progression over time of the sound occurrences. Accordingly, representation by means of a sonogram is comparable with representation using musical notation.

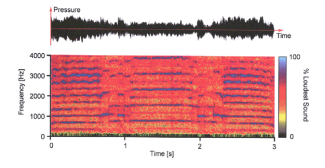

Subsequently in Edgar Rice Burroughs Inc v OHIM[39], the OHIM observed that its decision in Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer Lion Corporation’s Appeal relating to Community trade mark application No. 143891 was merely on obiter and should not be considered as a ruling on registration of sound marks through sonograms. In the said case, in 2004, the Applicant applied for registration “The Tarzan Yell” through a sonogram in Classes 9, 16, 25, 28, 38, 41 and 42. The mark was described as:

“The mark consists of the yell of the fictional character TARZAN, the yell consisting of five distinct phases, namely sustain, followed by ululation, followed by sustain, but at a higher frequency, followed by ululation, followed by sustain at the starting frequency, and being represented by the representations set out below, the upper representation being a plot, over the time of the yell, of the normalised envelope of the air pressure waveform and the lower representation being a normalised spectrogram of the yell consisting of a three-dimensional depiction of the frequency content (colours as shown) versus the frequency (vertical axis) over the time of the yell (horizontal axis).”

The sonogram/proposed sound mark is depicted herein below:

The examiner did not consider the sonogram as an acceptable graphical representation of a sound mark and relying on Shield Mark BV[40], stated that such a representation had to be clear, precise, self-contained, easily accessible, intelligible, durable and objective. The Applicant filed an appeal before Board of Appeal at OHIM. OHIM’s Board of Appeal dismissed the Appeal by holding as follows:

- The Court of Justice holds that trade mark may consist of a sign which is not in itself capable of being perceived visually, provided that it can be represented graphically, particularly by means of images, lines or characters and that its representation is clear, precise, self-contained, easily accessible, intelligible, durable and objective.

- In case of sound marks those requirements are satisfied where the sign is represented by a stave divided into measures and showing, in particular, a clef, musical notes and rests whose form indicates the relative value and, where necessary, accidentals.

- In the ‘Shield mark’ case, the Court did not expressly consider sonograms or sound files but the representation must in any case comply with the requirements that it be clear, precise, self-contained, easily accessible, intelligible, durable and objective.

- The requirements concerning a graphic representation of the mark serve a dual purpose, namely to define the precise subject-matter of protection granted and that entry of the mark in the Register makes it accessible to authorities and the public, who must be able to ascertain what is protected.

- Verbal circumscription of the mark as a ‘yell of the fictional character Tarzan’ is not a ‘clear’ and ‘self-contained’ representation of the sound itself.

- Spectrogram as filed does not fulfill the criterion to be ‘self-contained’.

- With regard to the function of the CTM register as a public Register, the notion of ‘self-contained’ means that third parties viewing the CTM Bulletin should on their own and without additional technical means be able to reproduce the sound or at least to have a general idea of what the sound is. Nobody can read a spectrogram as such.

- It is impossible to deduce from the image as filed at what exact frequencies this occurs. It is also impossible to recognize from the image as filed whether the sound phenomena depicted therein is a human voice or something else, e.g. the tune of violins or bells or a dog’s bark. The pressure curve reproduced on top of the coloured spectrogram image merely shows the relative variation of loudness but does not allow one to discern any specific ‘sound’ or melody.

- It is unlikely that anybody, even a superior specialist of spectrograms, could, on the basis of the spectrogram alone and without technical means, reproduce the sound.

- The representation is not easily accessible. The image does not make it possible for a competitor to transform the image into a sound, at least in his brain for himself, or otherwise by transforming it into a sound through technical means.

- The Board does not see any technical means by which such an image, which allegedly constitutes the graphics of a sound and allegedly was produced by technical means than can transform sounds into ‘spectrogram’ images, could be retransmitted or re-converted into a sound. It is not enough if the image filed would unambiguously and individually represent a given sound, as long as it is not possible to retransform the image into a sound.

- The Applicant’s reliance on Article of Wikipedia about sonograms is not relevant. Wikipedia states that spectrograms can be turned into a sound, but it does not state that this will be exactly the same sound as initially. It may be any sound and then the whole notion of spectrograms is practically useless.

- Under ‘Creating sound from a spectrogram’, the ‘Wikipedia’ article refers to various software programs. However, none of them promises that they could transform spectrogram files into the underlying sound.

- There are some very exotic software programs, none of them being part of a standard PC installation, that operate in the area of image/sound creation, but none of them pretends to have as its feature the ability to create spectrograms from sounds and also then reconvert the spectrogram into the same sound.

- Even if that were technically possible, it would still not render the filed representation ‘self-contained’ as this criterion requires the intelligibility of the sound without external technical support such as the installation of specific software.

- The contention that ‘everybody knew the Tarzan Yell’ is misplaced. This is for the reason that:

- Alleged Knowledge cannot make a non self –contained image capable of representing a sound.

- There is no evidence that everyone knows the Tarzan Yell.

- By making such an argument the Applicant relies not on a graphic representation, but on the memory in the mind of an average consumer who remembers the Tarzan yell. This means nothing but that the sound itself, if heard, is distinctive. But for that it must be able to be heard in the first place.

- The ‘Tarzan yell’ may take various forms. There have been around 6 Tarzan Movies. The applicant does not indicate which actor’s yell or the yell from which movie he wants to protect.

- Argument on well-known character of ‘Tarzan’ are on distinctiveness. However, the present matter is concerned with the representation and not unique source identification of the Tarzan Yell.

- The representation of a sound by any way other than musical notation is so difficult that the legislature has allowed filing of sound filed electronically. Which make it easily accessible and self-contained.

Presently, in the European Union, registration of sound mark is permissible not only through Musical Notations but also through sound filed as the Community Trade Marks Implementing Regulation provides for and allows for filing of sound filed in an electronic application since July, 2005 by virtue of Rule 3 (6).[41] Under the amended definition of ‘Trade Mark’ in the European Union Directive of 2015[42] sound has been specifically included.

The graphical representation requirement has been re-worded to “being represented on the register in a manner which enables the competent authorities and the public to determine the clear and precise subject matter of the protection afforded to its proprietor” and hence the Shield Mark BV test should continue to apply.

INDIA

In India, sound marks have been recognized as valid trade marks. In the year 2008, Yahoo Yodel became the first registered sound mark in India.[43] As per the Draft Trade Marks Manual a sound mark may consist of a sound and represented graphically by a series of musical notes with or without words. This mean that India has adopted the approach as laid down in the Shield Mark BV Case[44] of the European Court of Justice.

As per the Draft Trade Marks Manual, the acceptability of a sound mark in India must, like words or other types of trademarks, depend upon whether the sound is or has become a distinctive sign; that is whether the average consumer will perceive the sound as meaning that the goods or services are exclusively associated with one undertaking.

In India, the trade marks office does not intend to permit registration of sound marks without evidence of factual distinctiveness.[45]The draft of Manual of Trade Marks Practice & Procedure in India also provides guiding light to assess distinctive character of sound marks and seeks to bar the following sounds on the anvil that may not be accepted for registration as trademarks since these are incapable of distinguishing goods or services of one person from those of others:

- Very simple pieces of music consisting only of only 1 or 2 notes;

- Songs commonly used as chimes:

- Well known popular music in respect of entertainment services, park services;

- Children’s nursery rhymes, for goods or services aimed at children;

- Music strongly associated with particular regions or countries for the type of goods/services originating from or provided in that area.[46]

Till March 6, 2017, the Indian Trade Marks Office was relying on musical notations for the purposes of granting registrations to sound marks as held to be an appropriate way of graphical representation of sound marks in the Shields Marks BV case. The Trade Mark Rules, 2017 came into force on March 6, 2017 and apart from graphical representation requirement provided through musical notation requirement required for the first time submission of an audio file in MP3 format of the sound recording as mandatory for registration of sound recording.[47] Interestingly, the Rules do not use the term ‘musical notation’ but Form TM-A (Form for application for registration of Trade Mark)[48] mandatorily requires submission of specific musical notes pertaining to the sound recording.

6. COLOUR MARKS

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

In 1988 Congress amended the Lanham Act, revising portions of the definitional language. It enacted amendments against the following background (1) the Patent and Trademark Office had adopted a policy permitting registration of color as a trademark which was apparent from a perusal of the PTO Manual, January 1986 edition and May 1993 edition; and (2) the Trademark Commission had written a report, which recommended that: “the terms `symbol, or device’ not be deleted or narrowed to preclude registration of such things as a color, shape, smell, sound, or configuration which functions as a mark”. This strongly suggests that the language “any word, name, symbol, or device,” had come to include color.[49]

In the United States, the Supreme Court recognized the validity of non-traditional trade marks in Qualitex Co. v. Jacobson Prods. Co.[50] and in fact defined the contours of the The Lanham Act, 1946 qua registration of a color by holding that The Lanham Act 1946 permits the registration of a trademark that consists, purely and simply, of colour.

The question involved in the case was whether the Trademark Act of 1946 (Lanham Act), permits the registration of a trademark that consists, purely and simply, of a color. The Supreme Court of the United Stated concluded that sometimes a colour will meet ordinary legal trademark requirements.

Brief Facts of the case:

Petitioner (Qualitex) used a special shade of green-gold color on the pads that is made and sold to dry cleaning firms for use on dry cleaning presses since 1950s. In 1989, Respondent started using a similar green gold colour on its press pads. Petitioner filed a suit for unfair competition against Respondent. Petitioner also registered its special green-gold colour with the Patents and Trade Marks Office in 1991. Petitioner added a trade mark infringement claim to its suit for unfair competition. Petitioner won before the District Court. However, the Court of Appeal reversed the decision by holding that the Lanham Act does not permit registration of ‘color alone’ as a trade mark. The Courts of appeals across USA had different opinions on registrability of colour alone as trade mark.

The Supreme Court of United States observed as follows:

- Both the language of the Act and the basic underlying principles of trademark law would seem to include color within the universe of things that can qualify as a trademark.

- A color is also capable of satisfying the more important part of the statutory definition of a trademark, which requires that a person use or intend to use the mark: “to identify and distinguish his or her goods, including a unique product, from those manufactured or sold by others and to indicate the source of the goods, even if that source is unknown.”

- But, over time, customers may come to treat a particular color on a product as signifying a brand. And, if so, that color would have come to identify and distinguish the goods – i.e. to indicate their source – much in the way that descriptive words on a product can come to indicate a product’s origin.

- There is no principled objection to the use of color as a mark in the important “functionality” doctrine of trademark law.

- Sometimes color is not essential to a product’s use or purpose and does not affect cost or quality. This indicates that the doctrine of “functionality” does not create an absolute bar to the use of color alone as a mark.

- Qualitex’s green-gold press pad color has become distinctive, is not functional and there is no requirement that there is non competitive need for the green-gold colour to remain available in the industry.

- Unless there is some special reason that convincingly militates against the use of color alone as a trademark, trademark law would protect Qualitex’s use of the green-gold color on its press pads.

Hence, a perusal of the present decision demonstrates that a colour is registrable and protectable in United States of America if it has acquired secondary meaning.

EUROPEAN UNION

European Union recognizes Colour Combinations as well as Single Colours as registerable trade marks. The broader issue of non-conventionality remains largely in the area of single colour marks. The European Court of Justice, discussed the issue of registrability of single colour marks in the case of Libertel Groep BV v. Benelux-Merkenbureau[51]. The Applicant had applied for registration of the Colour Orange for telecommunications goods and services before Benelux Trade Marks Office (BTMO). The application form contained an orange rectangle and in the space for describing the trade mark, the word ‘orange’ was mentioned without reference to colour code.

The BTMO provisionally refused the trade mark registration and observed that unless the Applicant demonstrates that the mark has acquired a distinctive character. The Applicant approached the Regional Court of Appeal, Hague, Netherlands which was dismissed. The Applicant appealed to the Supreme Court of Netherlands. The Supreme Court of Netherlands prepared the following questions for opinion of the European Court of Justice.

“1. Is it possible for a single specific colour which is represented as such or is designated by an internationally applied code to acquire a distinctive character for certain goods or services within the meaning of Article 3(1)(b) of the Directive?

- If the answer to the first question is in the affirmative:

(a) In what circumstances may it be accepted that a single specific colour possesses a distinctive character in the sense used above?

(b) Does it make any difference if registration is sought for a large number of goods and/or services, rather than for a specific product or service, or category of goods or services respectively?

- In the assessment of the distinctive character of a specific colour as a trade mark, must account be taken of whether, with regard to that colour, there is a general interest in availability, such as can exist in respect of signs which denote a geographical origin?

- When considering the question whether a sign, for which registration as a trade mark is sought, possesses the distinctive character referred to in Article 3(1)(b) of the Directive, must the Benelux Trade Mark Office confine itself to an assessment in abstracto of distinctive character or must it take account of all the actual facts of the case, including the use made of the sign and the manner in which the sign is used?”

The European Court of Justice as preliminary considerations observed:

- Colour must satisfy three conditions: i) it must be a sign; ii) that sign must be capable of graphic representation; and iii) the sign must be capable of distinguishing the goods or services of one undertaking from those of other undertakings.

- A colour per se is capable, in relation to a product or service, of constituting a sign.

- The graphic representation must be clear, precise, self-contained, easily accessible, intelligible, durable and objective.

- A mere sample of colour does not satisfy the said requirements set out above.

- A colour sample may deteriorate over time. In cases of media, including paper, where it would deteriorate, filing of sample of colour does not possess durability.

- A sample of a colour, combined with a description in words of that colour, may constitute a graphic representation provided that the description is clear, precise, self-contained, easily accessible, intelligible, and objective.

- The designation of Colour using an internationally recognised identification code may be considered to constitute a graphic representation as such codes are deemed to be precise and stable.

- Where a sample of a colour, together with a description in words, does not satisfy the conditions for a graphical representation. That deficiency may, depending on the facts, be remedied by adding a colour designation from an internationally recognised identification code.

- The question whether a colour per se is capable of distinguishing the goods or services of one undertaking from those of other undertakings, is dependent upon whether or not colours per se are capable of conveying specific information, in particular as to the origin of a product or service.

- In that connection, it must be borne in mind that, whilst colours are capable of conveying certain associations of ideas, and of arousing feelings, they possess little inherent capacity for communicating specific information, especially since they are commonly and widely used, because of their appeal, in order to advertise and market goods or services, without any specific message.

- However, that factual finding would not justify the conclusion that colours per se cannot, as a matter of principle, be considered to be capable of distinguishing the goods or services of one undertaking from those of other undertakings. The possibility that a colour per se may in some circumstances serve as a badge of origin of the goods or services of an undertaking cannot be ruled out. It must therefore be accepted that colours per se may be capable of distinguishing the goods or services of one undertaking from those of other undertakings.

- It follows from the foregoing that, where the conditions described above apply, a colour per se is capable of constituting a trade mark.

The ECJ chose to decide the third question first and held that the reply to the third question referred must be that, in assessing the potential distinctiveness of a given colour as a trade mark, regard must be had to the general interest in not unduly restricting the availability of colours for the other traders who offer for sale goods or services of the same type as those in respect of which registration is sought.

Then ECJ answered the first question and (a) part of second question. The ECJ held that:

“The reply to the first question referred must therefore be that a colour per se, not spatially delimited, may, in respect of certain goods and services, have a distinctive character, provided that, inter alia, it may be represented graphically. The latter condition cannot be satisfied merely by reproducing on paper the colour in question, but may be satisfied by designating that colour using an internationally recognised identification code.

The reply to Question 2(a) must be that a colour per se may be found to possess distinctive character provided that, as regards the perception of the relevant public, the mark is capable of identifying the product or service for which registration is sought as originating from a particular undertaking and distinguishing that product or service from those of other undertakings.”

Question 2 (b) was answered by stating that the fact that registration as a trade mark of a colour per se is sought for a large number of goods or services, or for a specific product or service or for a specific group of goods or services, is relevant, together with all the other circumstances of the particular case, to assessing both the distinctive character of the colour in respect of which registration is sought, and whether its registration would run counter to the general interest in not unduly limiting the availability of colours for the other operators who offer for sale goods or services of the same type as those in respect of which registration is sought.

The fourth question was answered by stating in assessing whether a trade mark has distinctive character the competent authority for registering trade marks must carry out an examination by reference to the actual situation, taking account of all the circumstances of the case and in particular any use which has been made of the mark.

Thus, as per this decision of the European Court of Justice, it can be gathered that a mere sample of colour is not registrable and it is to be accompanied by a description in words. If still the said representation and description together fail to satisfy graphical representation requirement, the same can be fulfilled by relying upon Internationally recognized colour identification code. These requirements fulfill the ‘graphical representation’ test. However, the sign would still have to perform function of a trade mark for which it has to be distinctive. Due to the nature of colour marks and their perception amongst the relevant public, it has been stated that a colour mark can only be registrable on evidence of use. Therefore, a colour mark before its application has to be in use for the purpose of registration.

The same considerations apply to colour combinations as well. However, in cases of colour combination of two colours, ECJ has while building on the Sieckmann[52] requirement that the graphical representation of a trade mark be “precise and durable” in order to enable other traders to know the extent of the registrant’s rights, has held that a graphic representation consisting of two or more colours “must be systematically arranged by associating the colours concerned in a predetermined and uniform way”[53]. Specifically, the ECJ rejected Heidelberger’s claim to use blue and yellow “in every conceivable form”: this would not provide the “precision and uniformity” required by other traders.[54]

Under the amended definition of ‘Trade Mark’ in the European Union Directive of 2015[55] colours has been specifically included. The graphical representation requirement has been re-worded to “being represented on the register in a manner which enables the competent authorities and the public to determine the clear and precise subject matter of the protection afforded to its proprietor” and hence the Libertel[56] test should continue to apply.

INDIA

In India, colour combination has recognized as being capable of being a trade mark as way back as in the year 1977 in the case of Anglo-Dutch, Colour & Varnish Works Private Limited v. India Trading House[57] despite the term ‘colour combination’ not being included in the definition of the term ‘mark’ and ‘trade mark’. However, monopoly on a single colour was rejected. The Hon’ble High Court of Delhi observed that the colour combination in the said case is not descriptive but is distinctive and that a dealer can, have a trade-mark in combination of colours though not on an individual colour. The Hon’ble Court further observed that the combination of violet background and a large circle with white background and grey lettering is distinct combination of colours, and there is no legal bar to a person acquiring a trade-mark in such combination of colours for his containers.[58]

In 2003, the definition of the word ‘mark’ was amended in the newly enacted Trade Marks Act, 1999 to include combination of colours. Therefore, it was unclear as to whether single colour mark was registrable or not. Further, the term ‘trade mark’ in the Trade Marks Act, 1999 required ‘graphical representation’ as an essential attribute to qualify a ‘mark’ as ‘trade mark’. It was unclear as to what was the test in India, qua a graphical representation of colour.

In 2015, the draft of Manual of Trade Marks Practice & Procedure was released by the Indian Trade Marks Office. The requirement of the Indian Trade Marks Office is quite akin to European Court of Justice decision in the Libertel[59] case as it requires the exact description of the colour combination as per International Classification System of Colours for the purposes of registration. The Trade Marks Office also requires that the Applicant must also provide a concise and accurate description of the trade mark on the application. The description should state precisely what the mark consists of and how the description relates to the representation. The Manual also provides for an illustrative example. The same is reproduced herein: “The trade mark consists of a maroon colour applied to one half of a capsule at one end, and a gold colour applied to the other half, as illustrated in the representation on the application.”

However, the combination of colours must be distinctive either inherently or should have become distinctive by use. The Manual also clarifies that a single colour is also entitled to registration and is only protectable on evidence of use as it lacks the inherent capability of being distinctive. The same is entitled to registration if it serves as a badge of origin. The Manual provides that Marks consisting of a single colour will usually be liable to objection under Section 9(1)(a) of the Trade Marks Act, 1999. A perusal of the manual demonstrates that a colour/colours mark should be distinctive of trade source, ascertainable and non-functional. In case of colours, the threshold of evidence to claim exclusive rights is much higher.

As far as protection of colour combination in cases of passing off is concerned, the Division Bench of the Hon’ble High Court of Delhi in Britannia Industries Ltd. v. ITC Ltd.[60]has observed that the appropriation of and exclusivity claimed vis-à-vis a get-up and particularly a colour combination stands on a different footing from a trade mark or a trade name because colours and colour combinations are not inherently distinctive. It should, therefore, not be easy for a person to claim exclusivity over a colour combination particularly when the same has been in use only for a short while. It is only when it is established, may be even prima facie, that the colour combination has become distinctive of a person’s product that an order may be made in his favour.

As far as protection of single colour mark is concerned, the judicial view has been slightly contradictory. In Christian Louboutin SAS v. Pawan Kumar and Ors.[61], Hon’ble High Court of Delhi in an ex parte matter the RED SOLE mark of the Plaintiff was granted protection. A comparison of Plaintiff’s registered mark with the photograph of Defendant’s registered mark is provided herein below:

|

Plaintiff’s Registered Mark |

Product of one of the Defendant |

|

|

However, another co-ordinate bench of the Hon’ble High Court did not agree with the said decision in respect of the same mark in Christian Louboutin SAS vs. Abubaker and Ors.[62] by stating that use of a single colour of the Plaintiff does not qualify the single colour to be a trademark in view of provisions of the Trade Marks Act, 1999 and dismissed the suit.

The decision was appealed but the Division Bench of the Hon’ble High Court did not make any comments on merits of the matter but restored the suit.[63]

7. SHAPE MARKS

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

In United Stated of America, the decision of the United States Supreme Court in the case of Wal-Mart Stores v. Samara Bros.[64] is considered the seminal law on the subject of trade dress which includes shape marks. As per the Supreme Court of the United States, there is a distinction between a product design and packaging.

The Supreme Court observed that the product design can never be inherently distinctive. In order to register a shape mark, it is important that the shape should have acquired distinctiveness and the shape does not represent a functional feature of the product.[65]

In addition to the routine registration requirements, a registration of shape mark in United States requires a description of the mark stating clearly and accurately what the mark comprises along with a drawing of the mark. The drawing must depict a single image of the three-dimensional shape. The drawing must also show the shape in black on a white background, unless color is claimed as a feature. If color is claimed, the drawing must show the design in color[66]

If the claimed design has not yet acquired distinctiveness, the applicant may seek registration on the Supplemental Register which is reserved for marks, such as shapes/product configurations that are capable of serving as trademarks, but have not yet acquired distinctiveness. Registration on the Supplemental Register offers benefits, such as serving as nationwide notice of the registered design.[67]

It is pertinent to mention that the registration of a shape mark protects the ascertainable shape and not all the features provided within that shape which could be functional in their placement. For example, in Gibson Guitar Corp. v. Paul Reed Smith Guitars, LP[68], Court refused to extend protection of shape to other features of the guitar, such as the placement and style of knobs and switches.

EUROPEAN UNION

Over the years, European Court of Justice and European Union Intellectual Property Office have provided decisions and guidance on how to determine inherent distinctiveness of shapes of products for the purposes of trade mark registration. Most of the decisions in respect of shape marks have involved rejection of shapes where the owners have not filed supporting documents of use to corroborate a claim of distinctiveness.[69]

In Koninklijke Philips Electronics Ltd. v. Remington Consumers Products Ltd.[70], the Plaintiff was the registered proprietor of the following shape mark:

In 1966, Philips developed a new type of three headed rotary electric shaver. The three headed shape was registered as a trade mark in the year 1985. In 1995, Defendant started to sell a shaver with three rotating heads shaped similarly to the registered trade mark. Plaintiff filed a suit for infringement of trade mark and Defendant filed a revocation for removal of trade mark.

The High Court of Justice of England and Wales, Chancery Division, ordered revocation on the ground that the mark was:

- incapable of distinguishing the goods of Plaintiff from others;

- was devoid of distinctive character;

- mark consisted exclusively of a sign which served in trade to designate the intended purpose of the goods;

- was necessary to obtain a technical result

On appeal of the Plaintiff, the Court of Appeal referred decided to stay proceedings and referred certain questions to the European Court of Justice for determination.

The European Court of Justice held that:

- where a trader has been the only supplier of particular goods to the market, extensive use of a sign which consists of the shape of those goods may be sufficient to give the sign a distinctive character in circumstances where, as a result of that use, a substantial proportion of the relevant class of persons associates that shape with that trader

- It is for the national court to verify that the circumstances in which the requirement under that provision is satisfied are shown to exist on the basis of specific and reliable data.

- Signs which consist exclusively of the shape which results from the nature of the goods themselves, or the shape of the goods which is necessary to obtain a technical result, or the shape which gives substantial value to the goods cannot be registered or if registered are liable to be declared invalid.

- Where the essential functional characteristics of the shape of a product are attributable solely to the technical result, Article 3(1)(e), second indent, precludes registration of a sign consisting of that shape, even if that technical result can be achieved by other shapes.

Most importantly, the European Court of Justice held that a shape whose essential characteristics perform a technical function should be freely available to all. Shape of goods had always been recognized statutorily in European Union at least since 1989. The issues have arisen as to its registrability and its protection. Shape marks are not inherently registrable. However, it is easier to register a shape mark if the Applicant proves secondary meaning. Under the recently enacted Trade Marks Directive of 2015, like the earlier Trade Marks Directive, a sign which consist exclusively of:

(i) the shape, or another characteristic, which results from the nature of the goods themselves;

(ii) the shape, or another characteristic, of goods which is necessary to obtain a technical result;

(iii) the shape, or another characteristic, which gives substantial value to the goods are liable to be refused registration.

INDIA

The definition of the term ‘mark’ under the Trade Marks Act, 1999 applicable to India includes the term ‘shape’[71]. The term ‘shape’ was added in the definition of the word ‘mark’ only in the year 2003. However, the registrability and protectability of shape marks depends upon certain contingencies and riders which have developed through statutory restrictions and precedents.

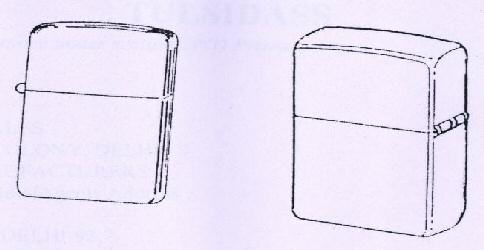

For the purposes of registration, two-dimensional graphic or photographic representations of the Shape Mark are to accompany the application.[72] Different perspective views of the shape are to be submitted. At times, the Registrar may even require a specimen to be submitted.[73] One illustrative example of a registered shape mark in India is of the Zippo Lighter. The registered mark is reproduced herein below:

In certain cases such shapes, may not be registered as a trade mark in light of the specific exclusion of certain shapes from registration under Section 9 (3) of the Trade Marks Act, 1999. The same are identical to the ones mentioned in Trade Marks Directive of 2015 of European Union as mentioned above.

The effect of functional feature of the shape makes it difficult for protecting the same through an action for passing off, even if the same has acquired goodwill and reputation. This is for the reason that the product in question will not be manufactured unless that shape is utilized and hence the shape would become generic to the good in question. In India, unregistered shape marks have protected by instituting suits for passing off.